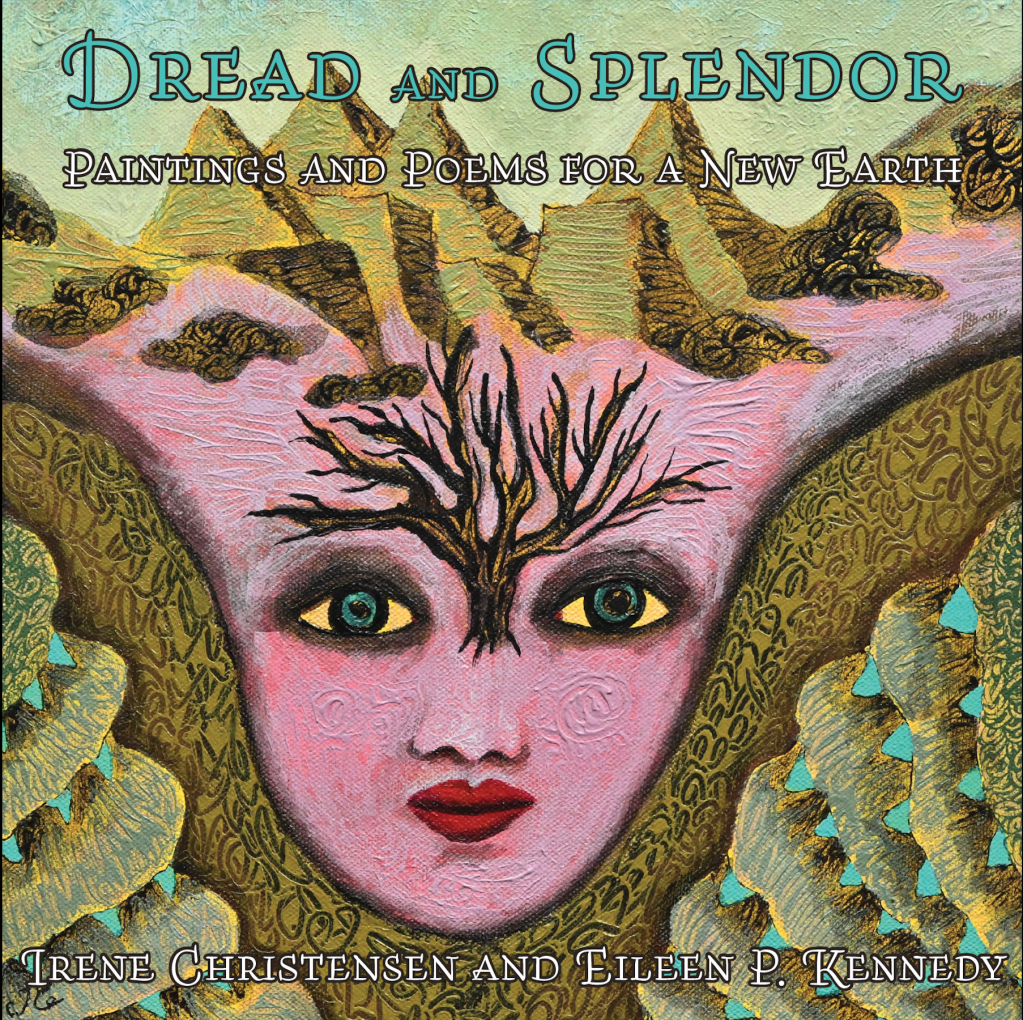

Dread and Splendor: Paintings and Poems for a New Earth is now out from Shanti Arts Press.

My collaborator, Irene Christensen, and I have been working on this book together for several years. We met at an artist colony in Costa Rica, with a shared appreciation for the natural beauty. of the rain forest where we lived.

I was there for the creation of these wonderful paintings about the feminine presence at the heart of the environmental movement. I started writing poem responses to the paintings. Irene took an interest in my writing and I gave her a copy of one of my books, Touch My Head Softly. In response she gave me the painting, “Volcano Flower,” about the Arenal Volcano, a shared experience. This exchange was the start of the book.

I will be reading from the book at several readings this spring. Some readings are live and on zoom:

.Thursday, April 23 at 7 pm at Amherst Books, 8 Main Street, Amherst with Sharon Tracey, author of Chroma: Five Centuries of Women Artists and Land Marks, both from Shanti Arts.

.Saturday, April 25 at 2 pm at Jones Library (temporary address 100 University Drive) with Cheryl J. Fish, author of Crater and Tower (Shanti Arts, 2025) and in person at 101 University Drive, Amherst, MA.

.Tuesday, May 5 from 6 to 8 pm, Forbes Library Coolidge Room. Writer’s Night Out. In person at 20 West St., Northampton, MA.

.Saturday, May 9 at 4 pm with Jonathan Wright, Forbes Library Coolidge Room. Gallery of Readers, In Person and on Zoom at 20 West St., Northampton, MA.

.Sunday, June 7 at 2:30 pm, in Person at 324 Main St, Greenfield MA at the Lava Center Sunday Spoken Word. Doors open at 1:20 pm.

.Sunday, June 28 at 2 pm (Book Launch) in Person and on Zoom at Cherry Hill Co-Housing, 120 Pulpit Hill Road, Amherst MA.

https://shantiarts.co/uploads/files/jkl/KENNEDY_CHRISTENSEN_DREAD.html#gsc.tab=0